The History of Scrollathon (abridged)

New York-based artists and brothers Steven and William Ladd have collaborated on artworks ranging from the miniscule to the massive for over two decades. Their artistic practice, spanning drawing, sculpture, text, and bookmaking, is often made of textiles and beadwork and uses storytelling to express the deeper meaning of the work. Steven and William’s work has been featured in The New York Times, Architectural Digest and Art Forum and can be found in collections including the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Fidelity International, Agnes Gund, Saint Louis Art Museum and Musée des Arts Décoratifs.

In 2006 Steven and William founded Scrollathon as a way to empower and engage underserved communities through artistic collaborations. To date over 17,000 people from diverse ages, backgrounds and abilities have collaborated with Steven and William to create public artworks at locations including the commercial development City Point in Brooklyn, NY, the Mercedes-Benz Stadium in Atlanta, GA and The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts. Through partnerships, Scrollathon has received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Knight Foundation and Bloomberg Philanthropies. 2022 launches the National Scrollathon, uniting all 50 states, D.C. and 5 territories to illuminate America’s story through collaborative world class art coinciding with America’s 250th Birthday in 2026.

The History of Scrollathon (expanded)

“To actually have a part of your idea, your imagination, your soul and roll it up and have it be a piece of the art, is sort of a miracle.”

Deborah Rutter, President, John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts

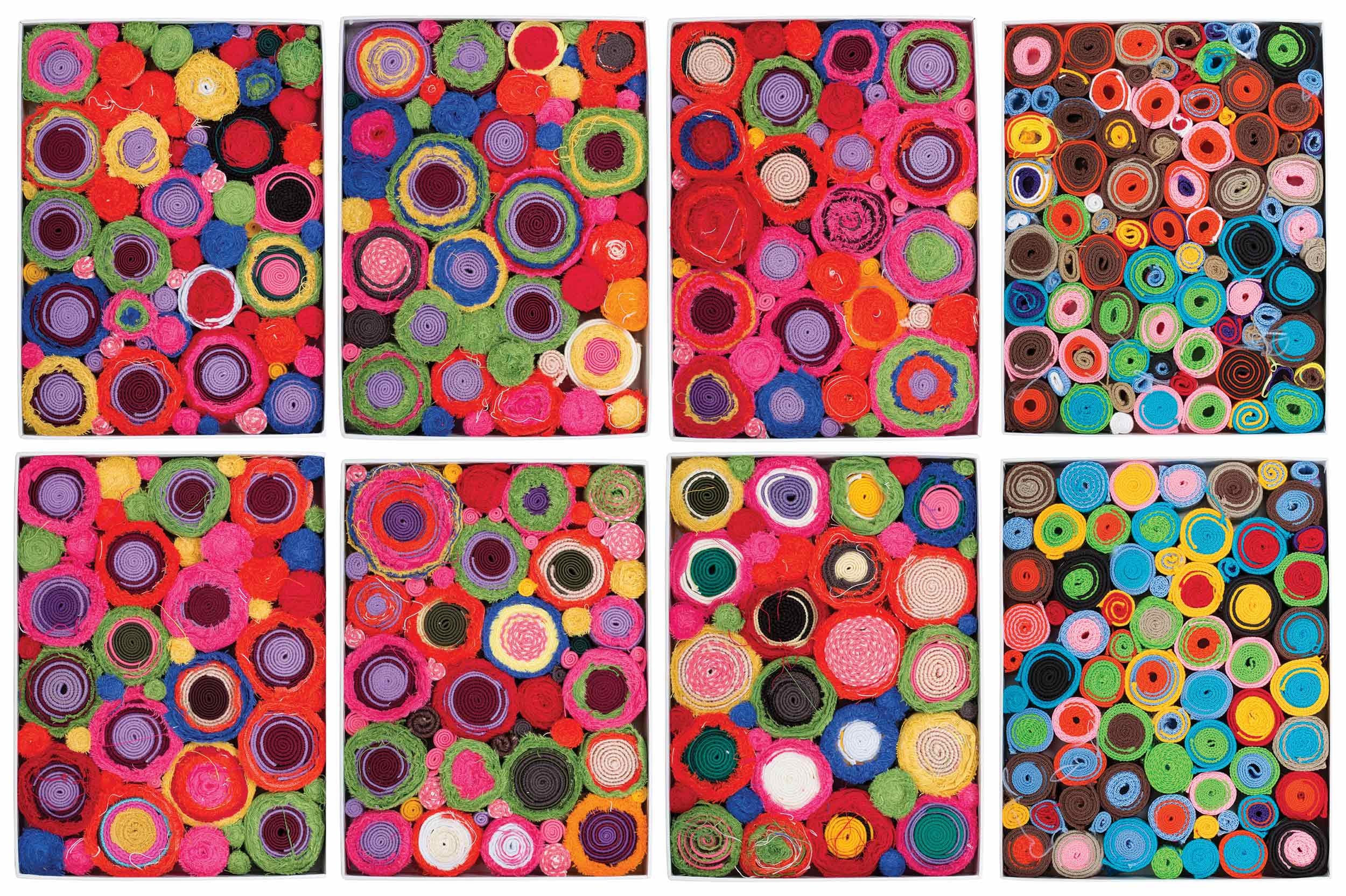

The Scrollathon was born out of artists and brothers Steven Ladd and William Ladd’s belief in the extraordinary capacities of every human being and the awesome power of community. 2006 marked the beginning of their integration of fine and conceptual art, design and craft with their passion to engage with people through hands-on educational collaboration. During Scrollathons, participants make an artwork to keep that they associate with a personal story, and share that story with the group, demonstrating how contemporary art can become a lens for personal storytelling. Then participants make components for a collaborative artwork and are photographed for a permanent record.

Beginning in the artists’ hometown of St. Louis, the program quickly took off in New York City, first with special education students in Brooklyn, those in the custody of the NYC Department of Corrections and with diverse communities across the United States and abroad. A Scrollathon in 2014 in conjunction with a major exhibition at the Parrish Art Museum received funding from the National Endowment for the Arts and expanded the program to over 1,100 participants in a single community for the first time. In subsequent years, Scrollathons have reached thousands more and created epic artworks celebrated by the communities where they are installed. A 2015 Scrollathon and commission for a 40 by 40-foot permanent monument in Downtown Brooklyn with 1,000 participants expanded the artists’ vision about how to take intricately crafted objects onto a massive scale. The following year more than 900 participants from local Boys and Girls Clubs in Atlanta contributed to a 35 foot mural for the new Mercedes-Benz Stadium, again exposing Steven and William’s work to non-art mainstream audiences, including a national feature on CBS related to the 2019 Super Bowl.

In 2019 Scrollathon reached more people than in any previous year: over 3,750 participants in four States and the District of Columbia. Bloomberg Philanthropies Public Art Challenge funded a Scrollathon with Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School students, veterans and others affected by the gun violence in Parkland, Florida, promoting community healing. Middle schoolers, youths in detention centers and seniors collaborated on an artwork for an exhibition promoting the senses funded by the Dallas Museum of Art and the High Museum of Art, Atlanta. Diverse ethnic community groups, U.S. Army staff and kids in after school programs helped create a vibrant work for the new NBA Detroit Pistons practice facility. And during a two week festival celebrating The John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts REACH expansion, 750 D.C. residents made scrolls for a 20 foot artwork permanently installed in the new River Pavilion, contributing to a lasting legacy at one of the Nation’s most interactive and inspiring arts and culture destinations.

With 2020’s unique challenges, the Scrollathon was able to engage 126 participants in five facilities on Rikers Island to collaborate on an artwork presented at the exhibition The Other Side at the Invisible Dog Art Center. This lead to a commission in 2021 by NYC Department of Corrections leadership that continues into 2022. Looking ahead, the National Scrollathon aims to unite the 50 states, 5 territories and Washington D.C. for a monumental nation-wide arts collaboration aimed at sharing the collective stories of the American people through world-class works of art.

Utilizing humble materials, an environment of love and encouragement and the guarantee of success, Scrollathon continues to reach people of all ages, abilities and backgrounds. It promotes reflection, healing, joy and accomplishment, giving each participant a sense of being part of something greater than themselves.

RIKERS: FREEDOM, 2013. “The female detainees filled the box with scrolls then gathered around to title it. The energy became electric as they brainstormed aloud. ”Green. Sentenced. Prison. Incarcerated. Freedom. Freedom! Put your hands together on the work!” They joined hands on top of the scrolls, chanting “FREEDOM! FREEDOM!” and burst into applause.”

RIKERS: COLLEGE, 2012. “We asked the boys about their future plans. One wanted to go to college. Another definitely didn’t. A third with a felony conviction thought he wouldn’t be allowed to. We gave them as much warmth and attention as we possibly could.”

Scrollathon Background With Incarcerated Communities

In 2012 Steven and William’s work with a District 75 School led to a collaboration with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to bring the Scrollathon to the Robert N. Davoren Complex (RNDC) on Rikers Island. The Department felt their success with the District 75 kids, many of whom had been kicked out of other schools and were in danger of institutionalization or incarceration, would translate well to those young incarcerated men in RNDC. Early success there led to its adoption in other facilities including the George Motchan Detention Center (GMDC) and the Rose M. Singer Center (RMSC).

Their first experiences in RNDC with the adolescent male detainees presented unique challenges. The brothers had to modify their program to meet the security demands. Trimming to make scrolls had to be smaller than four inches, pins had to be replaced with rubber bands, and gang colors had to be avoided. They encountered stringent rules about entering the Island and had to remain flexible with scheduling to allow for frequent alarms and lockdowns. There were also emotional challenges, all while maintaining the positive and uplifting energy required to create an atmosphere of success and collaboration.

Next they paired their Scrollathons with A Road Not Taken, a program that identifies and centers on those in custody with substance abuse concerns, including both females and males of low socioeconomic status and those with mental illness. Engagement with young and adult females in RMSC resulted in several works, as the reception was so positive and the women continually asked that Steven and William return. It was here that they received clearance for detainees to keep individual works, giving them a tangible reminder of the experience.

The founder of A Road Not Taken requested they visit GMDC to work with the young adult males. By this time Steven and William had been cleared to distribute feedback forms, allowing them to learn more about the detainee’s feelings on the program and giving them a chance to reflect more on personal stories in relation to the process of creating.

THE NEW NORMAL, 2017. We worked at the Manhattan Detention Complex on a year-long project with LGBTQ+ inmates. They were very engaged. When I asked one to share the title of their scroll, they said, “The name of my scroll is ‘The New Normal.’ Everyone always told me I was abnormal. But now I am ‘The New Normal.’”