In 2012, Steven and William Ladd embarked on a collaboration with the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene to bring Scrollathon to the Robert N. Davoren Complex (RNDC) on Rikers Island. The Ladd’s earlier success with kids at a District 75 school, many of whom had been expelled from other schools and were at risk of institutionalization or incarceration, had paved the way for their work with the young incarcerated boys in RNDC. Achievements at RNDC led to the program’s adoption in other facilities, including the George Motchan Detention Center (GMDC) and the Rose M. Singer Center (RMSC).

The initial experiences in RNDC with adolescent male detainees prompted the template program for the Scrollathons that followed. Unique security challenges demanded modifications to the existing program. For instance, trimming for scrolls had to be shorter than four inches, pins had to be replaced with rubber bands, and specific gang colors had to be avoided. In addition, the Ladds were required to navigate stringent rules for entering the Island and had to remain flexible with scheduling, which was often altered by alarms and lockdowns. Added to the practical challenges, Steven and William had to balance personal emotional challenges with their unflagging effort to convey respect and positivity and to maintain the uplifting energy level required to create a successful, collaborative atmosphere.

To address the needs of those in custody, often struggling with substance abuse and mental illness, the Ladds paired Scrollathon with “A Road Not Taken.”

Engagement with young and adult females in RMSC resulted in several major works as reception to the initial program was so positive that the women in custody continually asked for Steven and William to return. This positive feedback led to clearance for them to keep their individual works, giving them a tangible reminder of a rare creative experience and its positive impact in their lives.

The success of “A Road Not Taken” prompted the founder of the program to request Scrollathon’s presence at GMDC to work with the young adult males. By this time, Steven and William had received clearance to distribute feedback forms, enabling them to learn more about the detainee’s feelings about Scrollathon and to reflect more deeply on the impact of personal stories in the creative process.

In 2017, the brothers installed printed reproductions of a collaborative work created by those in custody in the two RMSC units that helped make it. The same year also saw the expansion of their program to the Manhattan Detention Complex (MDC) where they worked with Restart Housing and the Transgender Housing Unit, the only dedicated housing facilities for transgender people in the city’s Department of Corrections.

Despite the challenges posed by the COVID-19 pandemic, Steven and William developed a packet that allowed those in custody to create their artworks and contribute a word instead of a scroll to a collaborative piece. With the incredible support of the Department of Corrections, the Ladds were able to engage with over 125 participants in five NYC facilities, resulting in the collaborative work titled “Jail Cell,” which became the center of Steven and William’s groundbreaking exhibition “The Other Side” at The Invisible Dog Art Center in the fall of 2020.

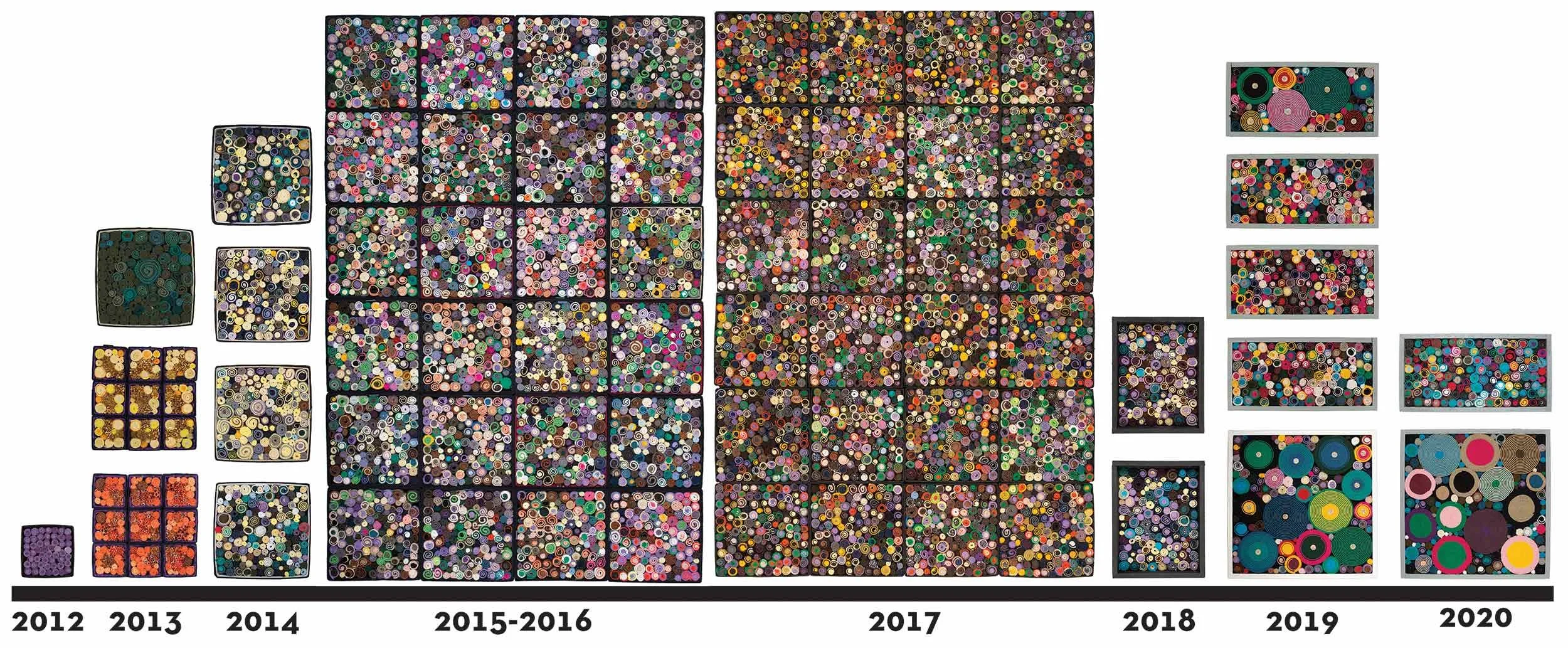

Scrollathon

NYC Department of Corrections

Rikers Island, New York 2012-2021

Robert N. Davoren Complex

Rikers Island, New York 2012

Rikers: Purple, 2012, archival board, fiber, tape, 5 ½ x 5 ½ x 2 ½ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Robert N. Davoren Complex

We were heading by bus to the Rikers Island Correctional Facility to collaborate with 16 to 18 year-olds at RNDC, a facility for adolescent boys. The rules on what we could bring into the facility were strict. Gang colors were forbidden, metal pins were replaced with rubber bands, cut fabric trimmings could measure no longer than four inches; all materials required written approval. The bus was running late and irate passengers yelled, “GO, GO!”, eager to be on time for visiting hours. On site, intense security protocols were followed before we finally got to the boys. Interior spaces were dark, somber, and sad. We sat around tables that were bolted to the ground, talking and making scrolls together with the boys. It was easy for them to succeed and realize how their individual contributions would help create a work of art.

We asked the boys about their future plans. One wanted to go to college. Another definitely didn’t. A third with a felony conviction thought he wouldn’t be allowed to. We gave them as much warmth and attention as we possibly could. Later, an art therapist from the jail wrote, “I keep meaning to email you to let you … “know that the boys in 4 Lower South really enjoyed their time with the artists. One … has asked me repeatedly when they will return and remarked on the natural way in which [Steven and William] interacted with them, and how they seemed so engaging and comfortable. This means so much to locked up kids who feel stigmatized almost all the time.”

Robert N. Davoren Complex and

Rose M. Singer Center

Rikers Island, New York 2013

Rikers: Freedom, 2013, archival board, fiber, beads, 10 ¼ x 10 ¼ x 2 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Rose M. Singer Center

Corrections Officers call out “Man on Deck!” as visitors enter the Rikers Island correctional facility, nicknamed “Rosies”, which houses women. About 25 women joined us to make art. They loved scrolling. After half an hour, they had filled a box with scrolls and gathered around the table to title the piece. The energy in the room became electric as they began brainstorming out loud. The scrolls were the same colors as their uniforms, and that’s where they began, with ideas spilling out faster and faster...”Green. Sentenced. Prison. Incarcerated. Freedom. Freedom!” One woman cried out, “Put your hands together on the work!” And these incarcerated women, of all different colors and backgrounds, joined hands on top of the scrolls, chanting “FREEDOM! FREEDOM! FREEDOM!” Then everyone burst into applause.

When we returned to work with them again, an older woman, maybe in her 80’s, said, “You came back,” and her eyes filled with tears. Later, at lunch, the program head Carmen told us that many of these women had never had a man in their lives live up to his word.

Rikers: College, 2013, archival board, fiber, rubber bands, 11 x 11 x 3 ½ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Robert N. Davoren Complex

Banana Mustang, 2013, archival board, fiber, beads, 11 x 11 x 3 ½ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Robert N. Davoren Complex

Robert N. Davoren Complex and

Rose M. Singer Center

Rikers island, New York 2014

Rikers: Hope and Faith, 2014, archival board, fiber, rubber bands, 10 ¼ x 10 ¼ x 2 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Rose M. Singer Center

Rikers: Shades of Rosies, 2014, archival board, fiber, rubber- bands, 10 ¼ x 10 ¼ x 2 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Rose M. Singer Center

Once, doing a project at Rosies, we recognized a girl as soon as we walked in. We had worked with her on the outside—on our big public project at City Point in Downtown Brooklyn. She came from a local school where, we had been cautioned, many students ended up institutionalized or incarcerated. But we didn’t say anything to her. You just never know what has happened to these individuals recently, or what they are feeling, so we allow them to give us our cues. Towards the end, she walked right up and asked how the Brooklyn project was going. We gave her a huge high five and showed her the beautiful pamphlet we’d brought about that project. It included her photo. And she was given permission to keep it.

Rikers: Maquette, 2014, archival board, fiber, rubberbands, 10 ¼ x 10 ¼ x 2 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at Rikers Island’s Robert N. Davoren Complex

Rikers: Thingamajig, 2014, archival board, fiber, rubberbands, 10 ¼ x 10 ¼ x 2 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with person in custody at Rikers Island’s Robert N. Davoren Complex

Rose M. Singer Center and

George Motchan Detention Center

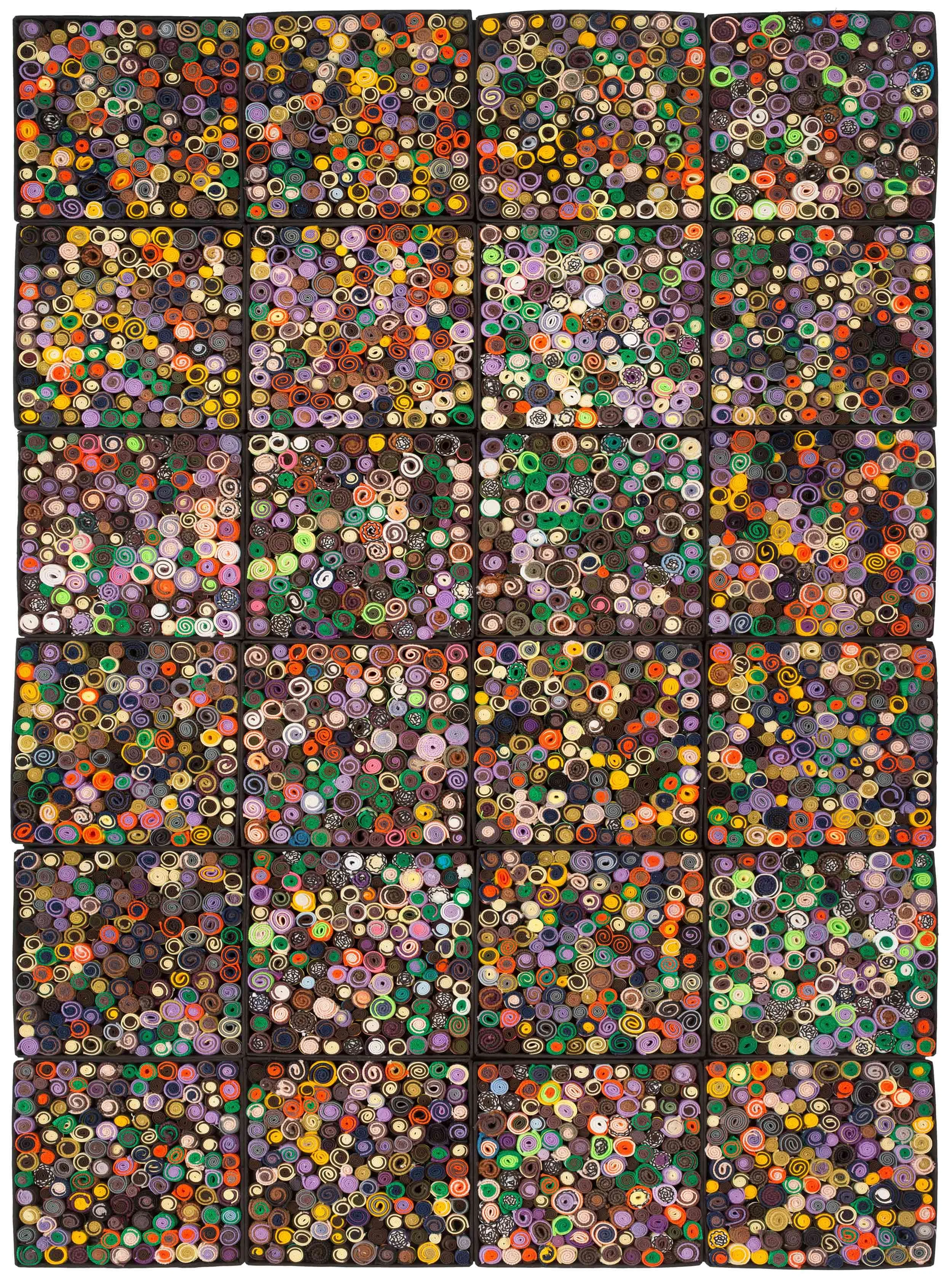

Rikers Island, New York 2015 - 2016

Invincible, 2016, archival board, fiber, rubberbands, ink, 41 x 61 x 3 ½ inches

Made in collaboration with 125 persons in custody and 375 other participants at the Rose M. Singer Center and the George Motchan Detention Center

“The name of my scroll is Invincible. That is the way I see my son. He is a person that doesn’t never stop going to his goals. [My scroll means] peace, stress free, doing something that will become a part of something bigger. [Steven and William] thanks so much for giving hope to each one [of us].”

-RMSC Scrollathon Participant

For Invincible, we made scrolls with 185 persons in custody in two women’s housing units over the course of a year. When the project was finished, we pushed for clearance to install a full-size photographic print in each unit. We finally scored a meeting with the warden, and he greeted us with a big smile. “I used to be the warden at RNDC,” he said. “I remember you guys.” We ran over to give him a big hug, and he gave us his approval. This was the only time we’ve received permission to install something permanent in the housing units.

We felt so proud as we carried the two giant metal photo reproductions through the hallways of the facility. Participants and officers gawked and told us they were beautiful. We couldn’t stop grinning as each reproduction went up. The participants we’d worked just gravitated towards the artworks and passed their hands all over their surfaces.

Manhattan Detention Complex

Transgender Housing Unit and Restart Housing Units 5N, 5S and 8W and

Nurses at the CHS Medical Trailer

Rikers Island and Manhattan,

New York 2017

The New Normal, 2017, archival board, fiber, rubberbands, glue, wood,

39 ¾ x 59 ⅜ x 2 inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at the Manhattan Detention Complex:

Transgender Housing Unit and Restart Housing Units 5N, 5S and 8W and with

Nurses at the CHS Medical Trailer on Rikers Island

We worked at the Manhattan Detention Complex on a year-long project in a housing unit strictly for LGBTQ+ persons in custody. They were more protected in this unit than in the general population. The unit has since been dissolved.

We often worked with the same participants multiple times, but one day a new person joined in and became instantly engaged. We could tell they felt welcome, and when asked to share the title of their scroll, they said, “The name of my scroll is The New Normal. Everyone always told me I was abnormal. But now I am The New Normal.” Immediately we chimed in, “You are all The New Normal!”

In the LGBTQ+ unit, two tables were pushed together, and we sat together with participants making scrolls from the pile of colorful trimmings heaped in the middle. Tiffany, a black trans woman who shares William’s birthday, revealed that they had nine brothers. In their mid-teens, they resolved to tell their family who they knew they really were. But before they could, they realized that their father already knew. One night at dinner, he looked around the table at his kids and declared that he was proud to have all boys—and no girls. They knew there was no place for them in the family. The next day, they left home and moved onto the street.

Manhattan Detention Complex

New York, New York, 2018

A Part of My Life, 2018, fiber, rubberbands, glue, wood, 9 ⅞ x 12 ⅜ x 2 ½ inches

Made in collaboration with participants at the Manhattan Detention Complex

Abstract Chaos, 2018, fiber, rubberbands, glue, wood,9 ⅞ x 12 ⅜ x 2 ½ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at the Manhattan Detention Complex

They were perched on a table bolted to the floor in a Manhattan corrections facility. We walked in smiling and invited them over where we laid out a pile of colorful fabric strips. One kept asking, “Be honest with me, are you scared to be here?” We said no. “That’s what’s up,” he said, and gave me an exploding fist bump. They joined us around the table and opened up to us as we made art together. “No one will work with us. Everyone is afraid. They don’t give us anything. We’re all in here for murder.”

The person in custody who “ran the house” wore about ten rosaries around his neck to prove it. Steven told him that William was a master bead worker, and the man nodded toward a person nearby and said that his friend was too. We had never received permission to bring beads into the jail because they could be manipulated for use in weapons, so finding out that these men were allowed to make rosaries and wear their beadwork was incredible to us. It was such a cool connection to us and our work.

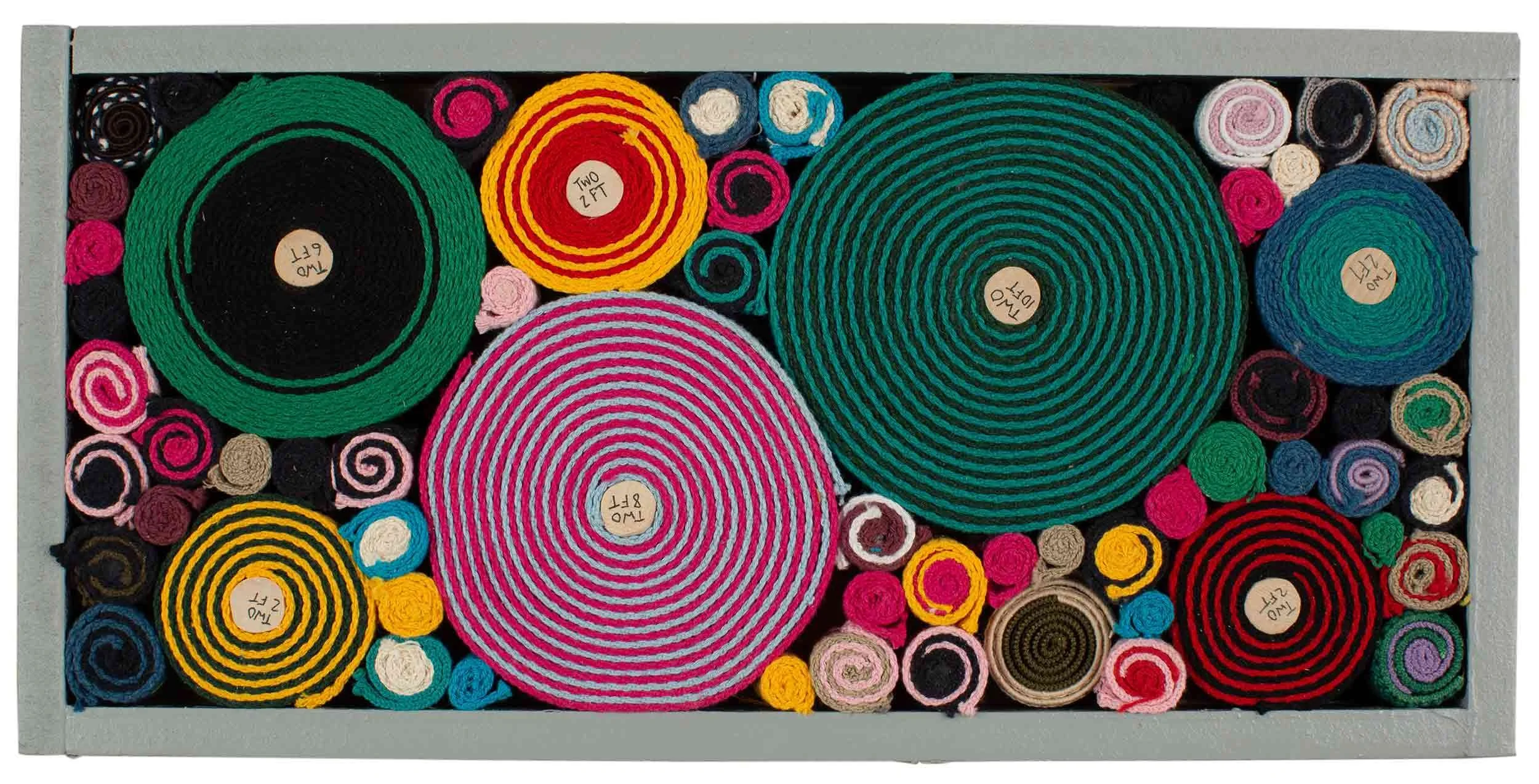

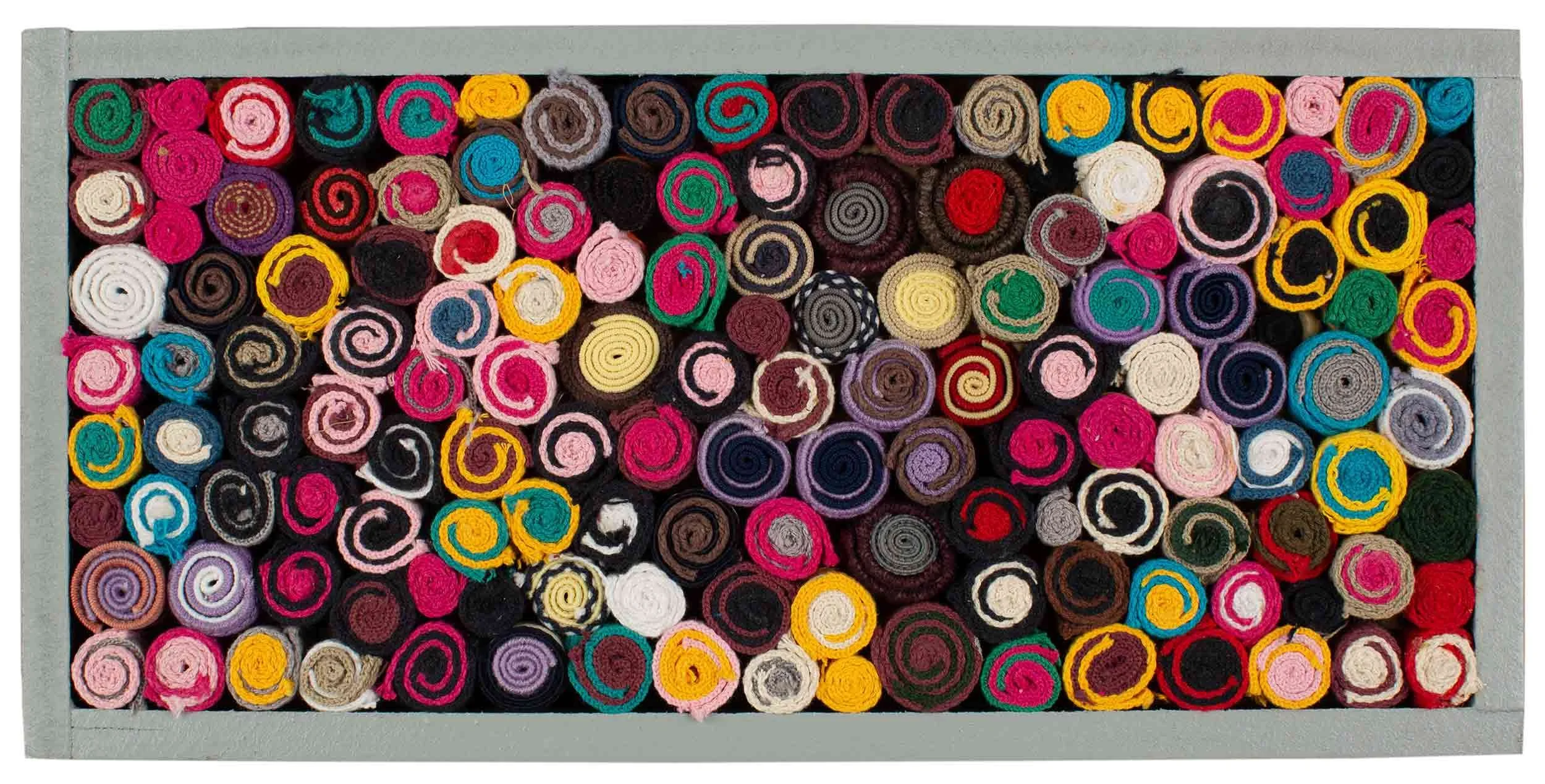

Manhattan Detention Complex

New York, New York, 2019

NYC DOC MAQUETTE 1, 2019, fiber, rubberbands, pins, glue, wood, 16 ⅛ x 16 ⅛ x 1 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at the Manhattan Detention Complex

This was the first time we were allowed to work with adult male participants at Rikers. For one hour, 15 guys sat around a table with us, grabbing trimmings to make scrolls, naming them, and telling us their stories. At the end of the session, the facility went on lock-down, so we stayed put, talking with them for another half hour. We asked one man about his hopes and dreams. He said he’d always wanted to own a service station. As a teenager, Steven’s first job was pumping gas, so he got all excited and said, “Let’s plan this out!” We talked about different steps this man might take over the next ten years in order to make his dream a reality. It was fun. At the end, he paused and said, “No one’s ever cared about me enough to have a conversation like this.”

Following another session with the adult men, we were waiting between two doorways for our escort out of the jail. We heard a man down the hall yelling to us, “Brothers! Brothers!” When he got our attention, he gave us a huge grin and called out, “I got my scroll! They tried to take it. But I said, ‘This is my scroll!’ And they let me keep it!” We were so happy.

NYC DOC MAQUETTE 2 - 5, 2019, fiber, rubberbands, pins, glue, wood; 7 ⅝ x 15 ⅝ x 1 ⅝ inches

Made in collaboration with persons in custody at the Manhattan Detention Complex

Jail Cell, (showing metal detectors and Pathway), 2020, various materials, 100 x 100 1/2 x 132 1/2 inches, made in collaboration with people in custody at Rikers Island, George R. Vierno Center, North Infirmary Command, Otis Bantum Correctional Center, Anna M. Kross Center, and the Manhattan Detention Complex and with 500+ people from our community on the outside

2020

Jail Cell

“What one word describes incarceration for you?”

The words lining this installation piece are responses to that question. Steven and William engaged with over 125 participants in five corrections facilities and hundreds more from the outside community to build these word blocks. We encourage you to think about this prompt and to write your word onto the wall behind you.

The summer of 2020, because of COVID, outside visitors were prohibited from entering correctional facilities, so we had to find a way to engage with those in custody without direct contact. Usually in our workshops, each participant makes a colorful scroll to keep and another as part of a collaborative piece. When we learned that they had access to colored pencils, we sent out packets that included a drawing of blank scrolls for inmates to color, so they were still able to create and keep their own work of art. We explained in the packet how we use art to tell stories and encouraged them to think of their own story as inspiration for their coloring, then to write that story in the space provided, and to sign and date their work.

And last, we asked them to send back anonymous responses to the prompt: “What one word describes incarceration for you?” We also collected responses from outside the prison, bringing inside and outside voices together. Walk inside Jail Cell, and you will be surrounded by those voices.

September 12- November 21, 2020

The Other Side reflects our experience as artists working with over 500 inmates at eight different New York City correctional facilities over a span of nine years. When it comes to incarceration, there is the “inside,” with inmates accused or convicted of crimes, and the “outside,” where the rest of us, guilty or not, live out our lives. We experience the inside with an outside perspective. Steven and William hope to bring a ray of light into the lives of the people inside these facilities.

Co-presented by The Invisible Dog Art Center, the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF) and Cristina Grajales Gallery

METAL DETECTORS AND PATHWAY, 2020

Various Materials

Moving into the jail, our hands were stamped with invisible ink. Keys and phones were forbidden. Everything we brought for the workshop required advance clearance. We passed slowly through a series of air lock-like spaces where one door closed before the next could open. Metal detectors flanked passageways which had a dividing line down the center. Our escort and a guard kept us to one side, and guarded inmates moved along the other, looking away because meeting visitors’ eyes was forbidden.

Jail protocol was shocking at the beginning. Every movement through every space is controlled. But we learned the rules, including how to wait patiently, sometimes for most of the day for only two hours of actual engagement time with inmates. We handed out pamphlets to corrections officers when they asked what we were doing. We were always waiting—for clearance, for escorts, for an inmate we hoped would participate in our project but hadn’t agreed. We learned to respect each inmate’s space while still offering encouragement by extending multiple opportunities to join us. We invited the officers to join us too, and those sharing a good rapport with inmates often did.

SCROLLATHON PROMPT

Over 500 people, including over 125 inmates from five NYC jails, have provided one word to the question: What one word describes incarceration for you? It has prompted storytelling and reflection. We hope you will contribute your word here to be included. Please write your word on this wall.

CROWN STOOLS WHITE, GOLD AND BLACK, 2020

Wood, metal, fiber

LWD 12 ½ x 12 ½ x 18 ¼ inches

Our first time at GMDC, one of the ten jails on Rikers Island, we worked with 19 to 21 year-olds. They seemed like kids to us. At their housing unit, the inmates placed chairs normally around our work table; but for one particular inmate, they stacked them up, enabling him to sit higher than the others. We learned that he was running the house—that he had the top rank in his unit. Because he wanted to participate in our project, the other inmates had his permission to join in. We found it fascinating how inmates used the chair as a way to demonstrate hierarchy and this inspired us to create a series of crown stools.

WATCHTOWER, 2020

Plywood structure upholstered in wool

LWD 135 ½ x 58 ½ x 119 inches

From the moment you arrive on Rikers Island you are confronted by powerful corrections officers ensconced in their imposing surveillance spaces. You encounter them again as you approach the jail complex. You stand outside and sort of wave to get their attention. They often take their time in acknowledging your presence. Every encounter is an opportunity for them to approve or deny your admittance. This process happens again once you are inside, and then again and again and again. By the time you finally reach the housing unit, you encounter a secured surveillance area where corrections officers keep watch over the lives of inmates and anyone else inside the jail. Observed constantly, we always tried to engage the officers whose job it was to be the eyes and ears monitoring these unpredictable spaces; the power to shut our project down or allow it to continue was always theirs.

ISOLATION, 2020

Various Materials

LWD: 110 x 81 ½ x 103 ½ inches

On entering the jail, we emptied our pockets into a locker. A sign beside it read ‘Load and Unload Weapons in Red Sandbox.’ It was not a joke.

Once when we arrived, there was a red light swiveling beyond the plexiglass barrier. The jail was on lock-down. There was no telling how long we would wait. Almost an hour later, our contact arrived and took us through an unfamiliar area. We passed a kind of holding cell—a 6 by 6 foot cage with a young inmate inside –and out escort asked him what he had done. He was the reason the entire jail had gone into lock-down, and we were on our way to his housing unit.

HOUSING UNIT, 2020

Cedar Structure with Outdoor Cushions

A housing unit is an area within a jail that houses inmates. It has a living area where inmates sleep in either individual cells holding one or two inmates or in a barrack style sleeping area with cots filling the room. The common area is where inmates eat, watch TV, hang out, exercise, and participate in programmed events. It is also where we hold Scrollathon. We created this seating area as a kind of common area – a place to congregate and engage with others during the run of the exhibition.

Once while working at the all-women’s jail, Rosies, on Rikers Island, we were in the common area where an inmate told us that when she scrolled with us, she felt like a family. Then she gestured towards the living area. “But back there,” she said, “we’re enemies.” As we were leaving, one woman turned to William and said, “I’ll never forget you.”

2021

A Fall 2020 Architectural Digest review of our exhibition (centered on nine years of work with people in custody of the NYC Department of Corrections (DOC)) triggered an unfathomable outcome: a visit from the Commissioner of Corrections! A team came ahead of the brass to inspect the street in and around The Invisible Dog Art Center, Brooklyn. We were both nervous and excited for what was about to happen.

The Commissioner, her Chief of Staff and Chief of Department—all female—toured the exhibition with us, touched by the heartfelt stories we had captured and inspired by the artworks that now encapsulated those stories. Commissioner Cynthia Brann told us she rarely encountered people not employed by the Department who have dedicated so much of their lives to working with those on the inside. She wanted to give us 100% access to Rikers Island to implement our dream project.

Our vision was a residency and we created an art studio and exhibition space in one of the facilities on the Island. The exhibition presented Collaborative Masterworks spanning a decade of engagements inside the DOC., our more personal artworks, as well as new works — a series of hand-beaded portraits of people we were inspired by during our years on the Island. Our hope was to increase morale and create a more positive environment among people living and working on the Island. People walking through the facility’s hallways would discover our space and, wide-eyed and fascinated, would ask, “What is this place!” We toured them through the exhibition, ending with the question, “What one word describes your hopes for the future?”

Rikers Portraits 2021 was made possible with the generous support of the Barbara and Donald Tober Foundation, Fieldstead and Company, Cristina Grajales Gallery, David Hughes and Mark Sappington. Special thanks to Lucien Zayan and the Invisible Dog Art Center, Pierre Rougier, Cynthia Brann, Hazel Jennings, Cecilia Flaherty, Carmen Gonzalez and Keziah Eddy.

We knew during our first visit to Rikers a decade ago that we’d continue this collaboration for the rest of our careers. Since 2012 we’ve worked with hundreds of those in custody—juvenile and adult, male, female and transitioning individuals—as well as correctional officers, staff and DOC leadership, sharing their stories through enduring and inspiring works of contemporary art.

How did the exhibition make you feel? Corrections Officer: “I feel like it gave me hope for the future and what this department can become if we all work together.”